A miracle, or a rather low bar?

Six months after surviving at-home cardiac arrest, one of the things I'm still very puzzled about is the "cognitively intact" label. What on Earth does it mean for me?

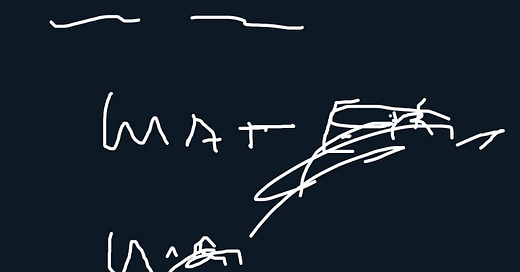

Upon waking up in the ICU after a two-day coma, I immediately began learning how to speak and write again so that I could advocate for myself. My dad later showed me the following triptych. Behold, my earliest attempts to draw on his tablet:

I am told the first drawing says “water.”

After being extubated I kept failing swallow tests. Nurses gave my husband a sponge on a stick that he could dip in water for me to suck on at regular intervals. I was not impressed and demanded, you know, a full glass of WATER. The stranger who scratched out her first two attempts to write this word and couldn’t quite complete the third attempt seems to have struggled to get her point across. I am told that her point was made abundantly clear at the time.

I don’t remember much about the next few days. The week or two before my cardiac arrest is a blank, too. I am told I always knew my husband in the hospital, and that I asked where he was whenever family and friends came to relieve him. I missed my dog. I tried to tell visitors that I was allowed to go to the bathroom myself (this was patently untrue—I couldn’t even stand up at the time!) I kept insisting that a closet door led to my bathroom. A nurse finally opened it, and I had to face the truth. Yep, it was a closet, just like they’d been trying to tell me. The big reveal shut me up for a bit.

For days, I couldn’t remember what had happened five minutes ago. I kept confusing the ICU with a visit to our local hospital for a seizure over a week prior to my cardiac arrest. People explained and re-explained that I’d had a cardiac arrest. I forgot again and again what they told me. I probably didn’t know what “sudden cardiac arrest” meant. I certainly didn’t understand what it meant for my present or my future.

I have a vague memory of signing forms before I was wheeled off to subcutaneous defibrillator (S-ICD) placement surgery. The wounds, bandages, and shooting pain afterwards caught my attention. The lumpy device in my chest continued to surprise me for weeks. To be honest, brushing the shock box under my skin still catches me off guard sometimes. It’s the constant, external, physical reminder that something quite terrible happened to my heart.

Eventually, my short-term memory improved. Near the end of my nine-day stay in the ICU, an all-important phrase appeared in the epileptologist’s notes. I was declared “cognitively intact.”

I started a new job exactly one month after my cardiac arrest. I was determined to prove I could return to “normal,” and nobody tried very hard to stop me. After all, I was cognitively intact! I slept for 12 hours per night to get through the first few days sitting online performing my virtual gig. Twelve hours was just what it took to have the mental stamina to meet and greet coworkers and clients. And I still stole a few cat naps in between longer meetings.

This all counts as cognitively intact, it would seem.

As the weeks turned into months, emotional baggage and exhaustion from the relentless onslaught of new symptoms, medical treatments, prescription side effects, and lost freedoms (such as driving) started to take their toll. I began treatment for PTSD. In June, four months after my cardiac arrest, I started experiencing a new type of seizure.

Note: I had pre-existing epilepsy. For years, I’d been considered luckiest-of-the-lucky in my epilepsy support group due to being fully controlled on a low dose of a single medication. I’d even regained my ability to drive. When COVID infection in late 2022 turned into acute myocarditis (which turned into breakthrough grand mal seizures, which turned into sudden cardiac arrest), I had status epilepticus at the hospital after being resuscitated. I seized for a very long time, well over 30 minutes. Doctors poured all manner of antiepileptic medications into IVs to stop the convulsing. Status alone could lead to permanent brain damage or death. Adding status to cardiac arrest makes my cognitive intact-ness almost unfathomable.

Most people who experience cardiac arrest do not survive. Among those who do, there is risk of neurologic dysfunction, brain injury, disorders of consciousness, neurocognitive deficits, changes in quality of life, as well as physical and psychological wellbeing.

Being cognitively intact is a tremendous blessing. But it does have its drawbacks. What is Buddhism’s First Noble Truth again? Oh yeah. Life is suffering.

My cardiac arrest itself was not stressful. Well—for me, I mean. I remember it as a moment of great peace and communion with the entire universe. I return to that spot in my house sometimes when living becomes especially hard. Now, I’m not saying cardiac arrest is some great thing. My body was in “acute distress,” according to the medical transcriptionist. And I feel terrible that it was so stressful for everyone else. It was stressful for my husband, who called 911 and started the CPR that prevented greater brain damage. It was stressful for the rescue workers and volunteers who stormed our house and used advanced lifesaving techniques to regain a pulse. It was stressful for myriad doctors, nurses, friends, neighbors, and family members. But my soul was somewhere peaceful.

My hospital art suggests that my stress started when I regained some level of cognitive function. Seeing “I want go home” scrawled in handwriting I don’t recognize is a horror I have trouble putting into words.

Is being declared “cognitively intact” the great miracle of my life? Probably. I started a newsletter today. I’m writing these words, there’s that. I visit with friends. I tend my garden. I listen to news and science podcasts. But I stopped working after several difficult months. I’m struggling to manage my emotions, establish a prescription regimen my body can tolerate, complete routine tasks, and find specialists who will treat me like a system instead of an assembly of random parts. I’m having small daily seizures. I intermittently have trouble moving and speaking.

I don’t know where this story will go next any more than I knew where the bathroom was in that hospital in Winchester. The progress, I suppose, is in knowing how much I don’t know. I’m learning a lot about what my brain and science are worth and also where they fail me. I’m starting, just starting, to catch glimpses of what else lays beyond. There are things I didn’t forget for one second in the ICU (such as who I love and where I’d rather be than in an ICU), and there are also things I understood afterwards for the very first time.

I’m currently in final editing stages for a memoir entitled Independence Ave. It’s the story of how I ended up being someone who looks and acts and just overall seems like she would be incredibly healthy but who collects chronic illnesses like it’s a professional sport. Maybe all the looking backwards inherent in memoir writing caused me to feel the pull towards a new project: writing into my unknown and unwritten future, however short or weird it may be.

Six months after my cardiac arrest, I still have no prognosis. I can’t find case studies similar to my situation to get a feel for what to expect. Medicine is doing a shoulder-shrug at my entire situation. Fed up with the lack of any realistic game plan from specialists I pay, I scheduled two weeks of inpatient testing at NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke next month. When I met with one of their doctors to discuss my new seizure activity, she asked how long my cardiac arrest lasted.

“24 minutes,” I replied.

She looked right at me then, eyes wide.

“Wow,” she said before she could stop herself.

I put some real stock in science. I hope science can help me. I take my mandatory five pharmaceuticals per day (assuming I don’t have a migraine…then it’s six). The copay for one of these pharmaceuticals would be $800/month if I wasn’t in an NIH study (thanks NIH!) I do all my therapist’s PTSD homework and I read lots of books. I read medical journal articles, too. I am the backseat-driver type of patient, I suppose.

I do my own research because I’m amazed sometimes by the simple questions that doctors don’t ask. I’ve already ended up back in the ER after being prescribed a harmful cocktail for my system. Medicine often fails to look at the full story. And the overall health of an organism is a full-story, big-picture problem. Science kept me alive—but am I what anyone should call “intact?”

I take the pills, but some days it feels largely superstitious. I’ve lost my blind, lifelong faith in science. Meanwhile, my mind and heart are opening to truth and assistance in all its many forms. So when my therapist talks about mindfulness, I don’t roll my eyes. I figure there’s a necessary spiritual component to my healing, if only because I beat so many odds. I say this as someone with a graduate degree in statistics—so yes, I understand randomness.

Someone could surely write off survival of my near-death experience as dumb luck, but that doesn’t help me. I need it to mean something. As Simone de Beauvoir wrote in her book The Ethics of Ambiguity:

“A life which does not seek to ground itself will be a pure contingency. But it is permitted to wish to give itself a meaning and a truth, and it then meets rigorous demands within its own heart.”

So here I am, a cognitively intact female fast approaching 40, seeking to ground herself so she can heal her mangled heart. I attend support groups for epilepsy and sudden cardiac arrest, and they help. Even among survivors and patients, though, there is often a lack of honest conversation about the emotional roller coaster of surviving chronic illness. We shy away from expressing the full loss and grief we experience and rush to express stories of resilience and recovery. Worse, we seek to solve each others’ problems without first acknowledging the fear and anger being shared.

So I resolved to write about my experience of survival one week at a time, as I live it. I figure I can most truthfully share the ups and the downs in real time. I hope this newsletter helps someone. I know that I could use more examples of openness from fellow survivors about what to expect, what helps, and what doesn’t.

I look forward to building this community and to hearing from others with chronic illnesses and near-death experiences. My guess is that if you have a body, and if you’ve ever had a health problem, there will be something you can relate to in my story.

I wish you all the best on your road to newfound health. The story you tell of your recovery efforts post cardiac arrest is so eye opening. Thank you for sharing.