Stumbling home sober.

Is “basal ganglia dysfunction” an onomatopoeia? It might be. Several months after surviving cardiac arrest, my new movement disorder looks pretty much like basal ganglia sounds.

I careened faintly left and right, trying to remain balanced on my two feet. Times like this, a third foot would be very welcome. I glanced down. My legs were slightly wider than hip-width apart, a telltale sign that balance was leaving me. My left hand started to flex outward and upward. My right swung ever so slightly wide from my torso. Anyone looking might reasonably have assumed that I was the drunk girl.

Instead, I’m the stone-cold sober girl. This is just how I walk when it’s approaching 7 p.m. And sometimes, when it’s 5 p.m. If I push myself in the garden or if yesterday was a particularly social day…maybe even in the morning.

Chris came back from ditching our empty drink cans and grabbed my wayward right hand to help me stumble home. We crossed our neighbor’s yard, the quiet street, and made it back to our own property. I was grateful to make it through the back gate before my gait fully went berserk. By the time I reached the kitchen porch, my arms and hips were waving around in the erratic dance rhythm that Chris and I are learning to treat as a matter of course.

Bright light still streamed through every window in the house while my husband and service dog helped me up the old back staircase. I sat on the floor of the bathroom to brush my teeth. I washed my face and awkwardly scampered into bed. I could hear the music across the street picking up and fell asleep just as the real party began.

I don’t remember anyone warning me that I might have trouble walking after my cardiac arrest. I was horizontal for most of the nine days I spent in the hospital—did they even test whether I could walk? I assumed that I was weak during my first few weeks home due to low ejection fraction and wounds from S-ICD surgery. I assumed that my ability to move would improve along with my heart’s recovery. Instead, there was an inverse relationship. The more activity my heart could tolerate, the more frequently my gait went wonky.

Pinning our hopes on a brain MRI and lots of testing at NIH this month, Chris and I alternate between concern, fatigue, and laughter about what we call my new “dance moves.” Think: those orange inflatable tube men outside car dealerships, especially the ones that aren’t given quite enough air to stand up straight.

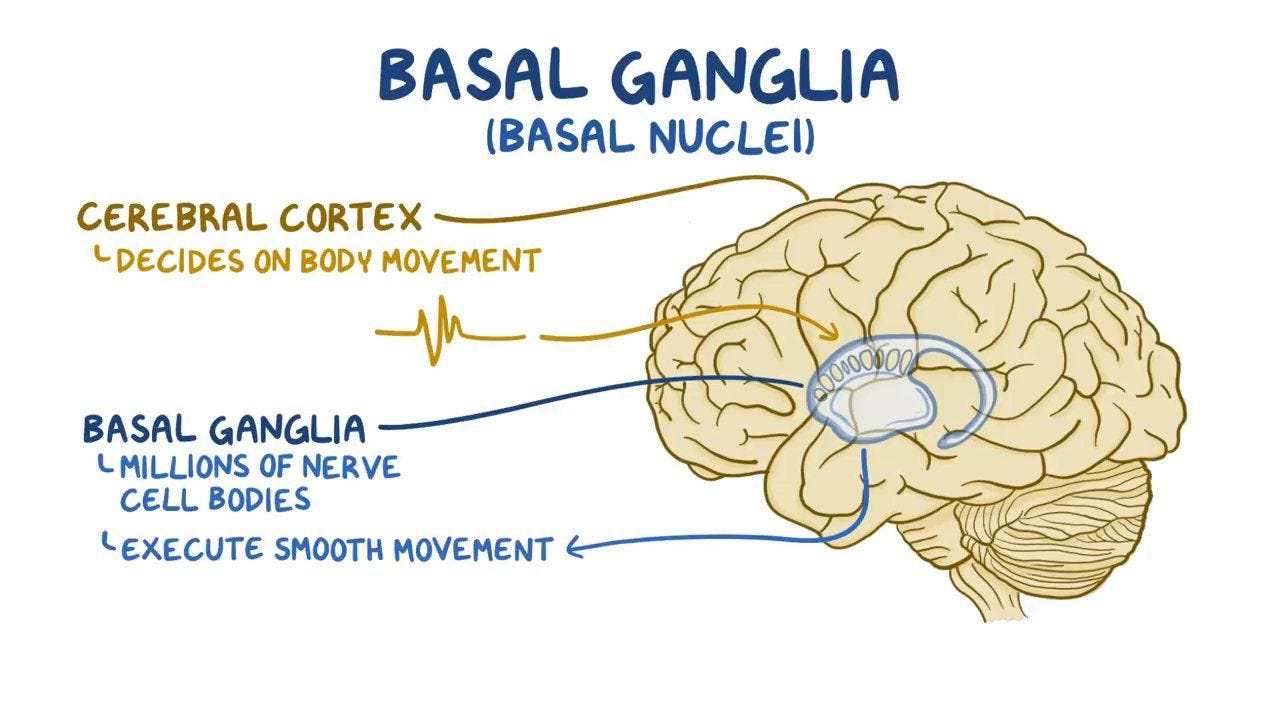

Are my dance moves post-hypoxic dance moves? At an office visit recently, one NIH neurologist suggested that they might be. European Journal of Neurology: “Post-hypoxic movement disorders after cardiac arrest are under-reported phenomena most probably related to basal ganglia dysfunction.”

Doctors decided not to do an MRI of my brain in the days immediately following my cardiac arrest, perhaps because a brain CT came back clean. Now, we have a massive investigatory problem on our hands. We weed through accumulated medication side effects, electrolyte imbalances, obscure seizure types, and potential degenerative damage to my basal ganglia or other parts of the brain. A lot could have happened during the 24 minutes that my brain was starved of oxygen in February. Like most things since the cardiac arrest: it’s TBD.

The one thing I do know is that there’s a huge difference between deciding to move and the smooth execution of that movement. There are times that I will my feet to go, and they don’t. I just stay stuck in place. At first, Chris didn’t know why I wasn’t moving or speaking sometimes, which led to many frustrating interactions. Now, it’s often his first guess if I’m being weird: “are you stuck?”

There are many more times that I move, but very badly. I’ve become more brazen as I get used to the new gait and realize I won’t necessarily fall over, or at least not quickly. I seem determined to learn how to move forward even if it feels like I’m suddenly inhabiting someone else’s nerves and muscles. Usually this leads to shaking limbs, sudden fatigue, and even less balance. I’m still in the early, experimental stages of pushing my own limits. I understand why my husband wants me to sit down and wait it out. He understands why I often shake my head and force the issue.

A few months ago, ataxia (or lack of coordination) was often the first sign that convulsions were about to begin. Chris and I assumed the two were wholly linked. Now, having swapped one of my seizure medications (generic Keppra) for its newer, more pinpointed (and more expensive) cousin Briviact, convulsions are better controlled. The movement difficulties have continued to increase and worsen. Ataxia is a listed side effect of Briviact, Keppra, and most of my other seizure and heart drugs. But who knows what’s going on in this body of mine. It’ll be interesting to see what NIH doctors find in my upcoming MRI and long-term epilepsy monitoring unit study.