Resuscitation

Attending a CPR class as an SCA survivor is a special (and eerie) experience that sparks some soul-searching

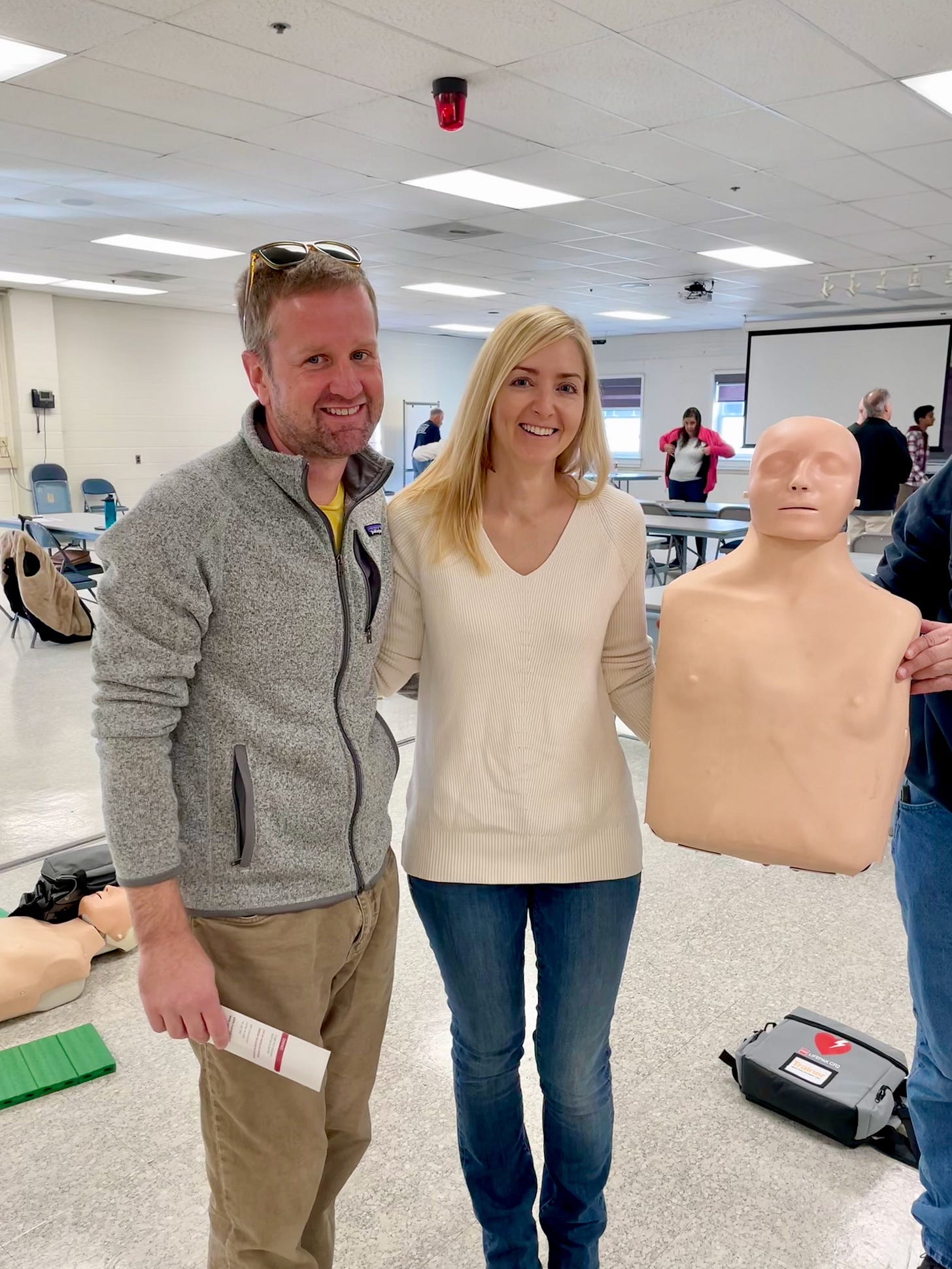

My husband and I joined some friends at a hands-only CPR class in Fairfax, VA last weekend. It was important to us to brush up on our understanding of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) best practices. CPR saved me several months ago, and I wanted to make sure I have the skills to return the favor to someone else someday. All in all, we both did a good job handling the somewhat awkward and PTSD-triggering experience of attending the training as co-survivors.

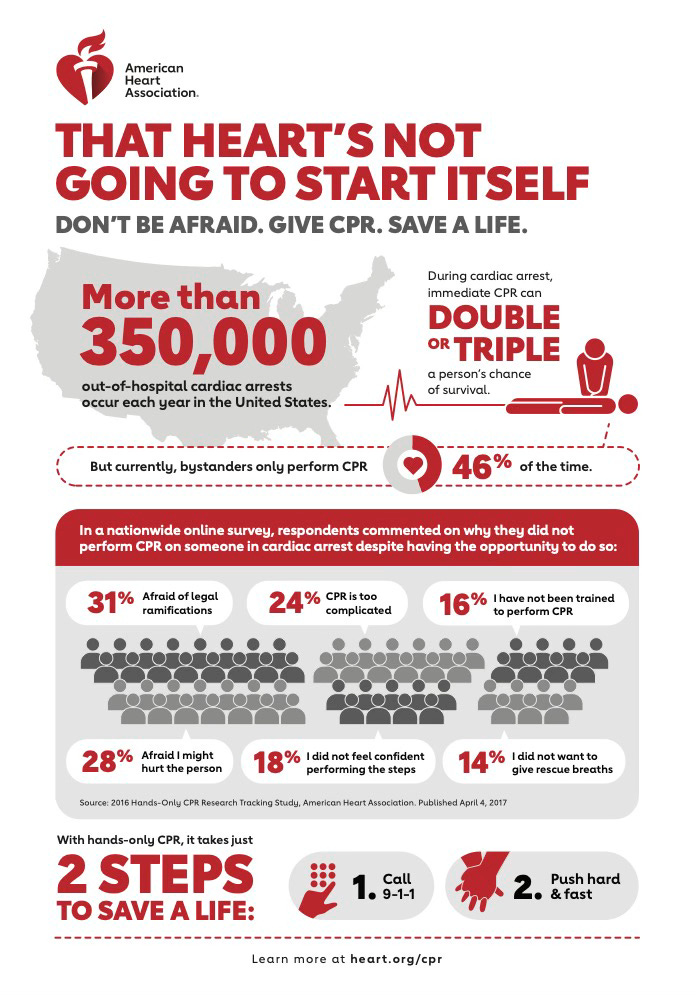

Our course was a short and sweet (90 minutes, $0) introduction. It drilled attendees about the most important things to remember in a cardiac arrest emergency. This includes: (1) How to tell if someone needs CPR (make sure they have no pulse); (2) Order of operations (call 911, place phone beside you on speaker, start CPR, then ask anyone else around to find a defibrillator (AED), etc.); (3) How to perform CPR (positioning your hands and body, 100-120 presses per minutes, 2 inches deep, etc.); and how to use an external AED machine.

The new thing I learned was that CPR is not intended to “bring someone back” by restarting their heart. You’ll need an AED for that. Or, you might get lucky and the heart might spontaneously restart on its own. But the purpose of CPR is to temporarily be someone’s heart. You do CPR to supply oxygen to the brain until EMTs arrive or someone locates an AED. You do CPR to prevent brain death.

This got me thinking. My own sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) lasted 24 minutes. In that 24 minutes, my husband performed CPR and rescue workers shocked me with the AED paddles 4 times. But still, 24 minutes passed in which I had no pulse and was not breathing. People have worse brain damage than me after a 5-minute SCA in a hospital. Why and how was I spared?

I’d originally read that brain death begins within 4 minutes of the heart stopping, and this was reiterated in the CPR course. CPR has the power to keep a person going for a very long time. The AWARE-II study published last month shows that despite severe lack of oxygen to the brain, some SCA victims have normal EEG activity (delta, theta and alpha waves) consistent with consciousness as much as 35–60 minutes into CPR! This also means that awareness may not always be absent during cardiac arrest. Researchers found that 39% of SCA survivors reported some level of perceived awareness; 9% reported transcendent experiences; and 46% reported other experiences including fear, persecution, hallucination, and emergence from coma.

I have no distinct memory of my SCA. I only remember a feeling of peace. But an EMT later told me that I grabbed her hand right before being loaded into the medevac. I may have looked unconscious otherwise, but some part of me was aware of the “acute distress” that’s cited in medical transcriptions from that day.

Per NYU's Parnia Lab:

From a biological perspective, cardiac arrest is synonymous with death by cardiorespiratory criteria, which is declared based on the absence of heartbeat and respiration and the loss of brain function. Deprived of blood flow and oxygen, the cells of the body begin their own process of death. Different cell types die at different rates. Contrary to previous notions that brain cells die within 5 to 10 minutes, evidence now suggests that if left alone, the cells of the brain die slowly over a period of many hours, even days after the heart stops and a person dies.

Paradoxically, it is the reintroduction of oxygen to deprived cells after the heart is restarted that causes the cells to suddenly die much more rapidly. The longer someone has been left without a heartbeat, the greater this cell injury process.

I find the bolded statement above absolutely fascinating.

This reintroduction-of-oxygen problem is what therapeutic hypothermia (cooling the body to around 90 degrees) exists to treat. The reason hypothermia works isn’t quite clear, but by slowing my body’s chemical reactions, doctors may have lowered inflammation in my brain. This practice likely helped me bounce back.

My own miracle is tiny compared to those with Lazarus syndrome, or “autoresuscitation” after failed cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Thirty-eight times since 1982, doctors have recorded someone being pronounced dead after resuscitation efforts are stopped, but then (minutes or hours later) their heart spontaneously restarted and they woke up. Wild! Lazarus syndrome is a good reminder of how little we really know about cardiac arrest or resuscitation. And also life, death, and being human.

After my own SCA, I tried to wake up from my coma before doctors were ready. Then, when I was finally allowed to wake up, I was a mess. The despair, fear, pain, and confusion of those first several days is (thankfully) quite foggy for me, but I feel in my bones that it was unbearable. Unbearable enough that my stomach turns every time I catch a glimpse, in the mirror, of the little round catheter wound on my neck.

I now find myself in the strange position of having a surgically implanted defibrillator (S-ICD) in my side that will shock me back to life if my heart stops again—and with a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order in my living will. The S-ICD was added before I really knew what was going on. With limited information about what had caused the SCA, my husband opted to have the S-ICD placed before I left the ICU (a smart move, b/c I certainly would not have gone back for one!) A couple months later, I added the DNR amidst horrific PTSD, in the hopes that I’d never have to go through another waking-up experience like the one in February. Many times, I even wished the S-ICD wasn’t inside of me, so that I could die peacefully next time. I don't bring this up because I want to die, or because I’m ungrateful that I survived, but because most of the world doesn’t understand how cardiac arrest affects a person, how long recovery really takes, or the sort of care that needs to be offered after leaving the hospital. How could it, when the survival rate from SCA is below 10%? There just aren’t many of us running around talking about our experiences.

These days, as I feel better and adjust to my new life, I start to think about removing the DNR from my living will. Then I remember the stories family and friends have told me about the ICU…and my first week home, when I could barely walk…the searing chest pain for weeks…and the agony I must have been feeling when I grabbed that first responder’s hand. So far, the DNR remains in place.

My chain of survival continues to amaze me, the more I learn about sudden cardiac arrest. I’d be honored to give someone else a second chance, if I was in the right place and the right time. But the “burning hoops” (as my brother called them) of working towards discharge and then back into a full life almost did me in on a spiritual and emotional level. Those burning hoops are still very much with me—both in what my brain consciously remembers, and in the shadows living in the memory cells of my heart.

What gets lost in the shocking magic of CPR and AEDs is that resuscitation isn’t over after the heart restarts. Just like the brain doesn’t die immediately when you lose your pulse, I don’t think your heart stabilizes immediately after you’ve returned to sinus rhythm and are declared cognitively intact. In my case, anyway, resuscitation is still ongoing.

Wow. Fascinating piece. Thank you for sharing this information, along with your experience!