Noncompliance or self-determination? You be the judge.

Goal-directed medical therapy and the decision to go my own way

My memoir, Independence Ave, recounts how it felt to show up for my first check-up after surviving sudden cardiac arrest (SCA). An imposing sign hung over the registration desk: HEART FAILURE CLINIC.

Wait, what?! Heart failure? Sure, my heart’s ejection fraction (EF), a measure of how well the heart is pumping blood, had plunged to 15% at one point in the ICU. I’d had a brush with death after contracting COVID-19, and I’d survived. Two weeks later, I was still very sore from defibrillator surgery and my EF was around 40%. I was young-ish, and I had no history of heart problems. I expected that it was only a matter of time until I got back to normal.

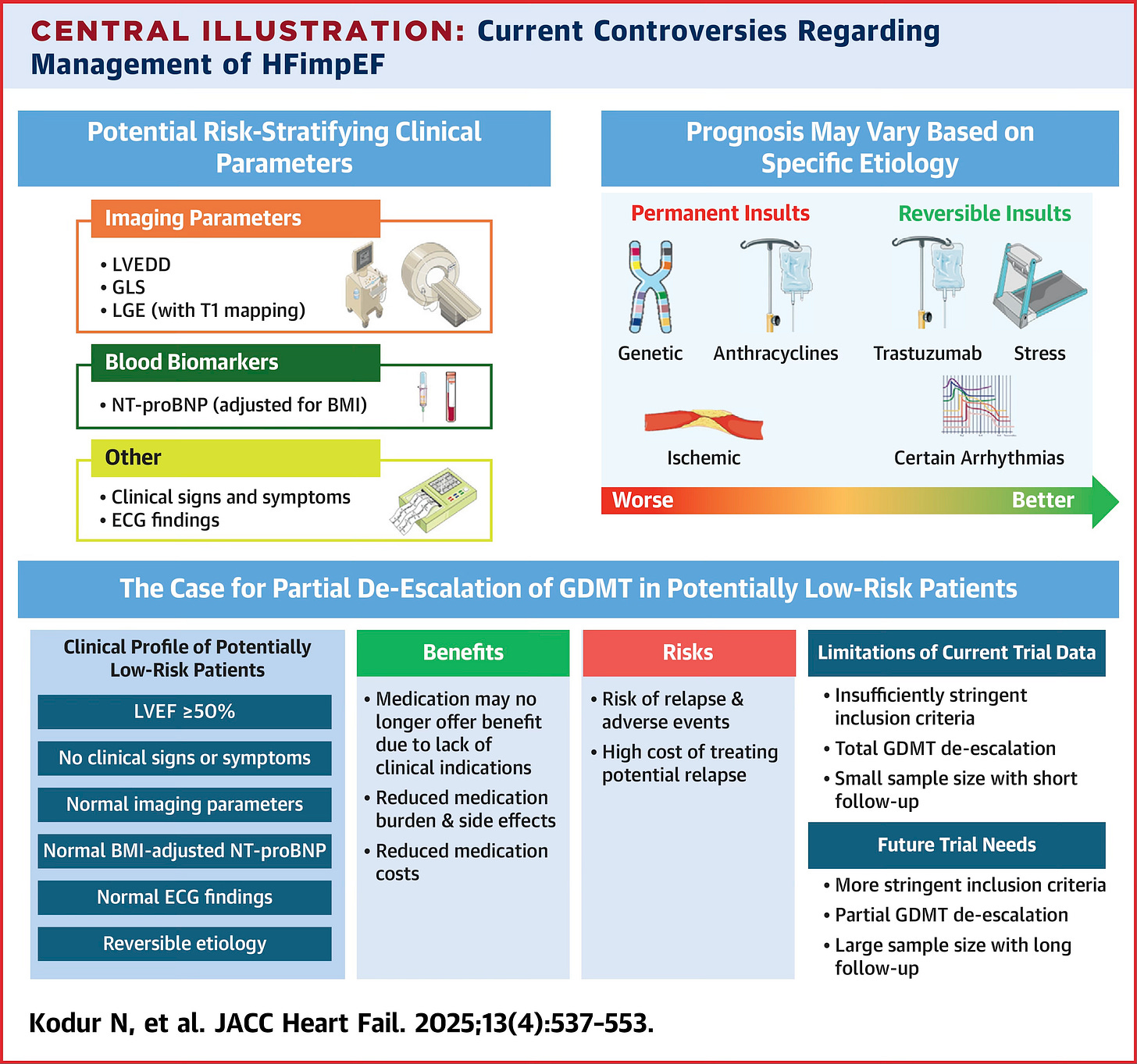

Modern cardiology had other ideas. That was the day I got tagged with a new chronic diagnosis: heart failure with improved ejection fraction (HFimpEF). Cardiologists only recently agreed about how to classify HFimpEF, declaring it: “an absolute improvement of LVEF [left ventricle ejection fraction] by ≥10% to >40%” (JACC). Many controversies remain, given that HFimpEF is under-researched compared to traditional heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. One thing is clear, though. HFimpEF is a temporary remission, not a full recovery. Twenty percent of those diagnosed with HFimpEF die, have a heart transplant, or suffer events that earn them a surgically-placed defibrillator within eight years (American Heart Association). We HFimpEF patients live a little longer, on average, than those with reduced ejection fraction. But our symptoms and hospitalization rates don’t normalize along with our EF percentages. EF is an important metric, but it is far from the whole story of how a patient (or even a patient’s heart) is faring

Since my event in 2023, cardiologists warn me time and again that my own heart will never go back to normal. My mitral valve is a little floppy post-SCA, which we monitor with yearly echocardiograms. My internal loop recorder shows premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), in which my heart beats out of rhythm every second or third beat, 5-10% of the time. This sometimes feels like fluttering or palpitations. Many people find PVCs uncomfortable, but I choose to find them endearing. I’m a sucker for a syncopated beat in music, so I just consider my heart a bit jazzy. My cardiologist isn’t concerned as long as the overall PVC burden stays at this level, so I choose not to worry either.

As a heart failure patient, what I care about physically is whether or not I can hike, walk, jog, etc. I can do those things decently well. My ejection fraction is estimated to be over 50% at last check, placing me at the low end of the normal range. At what point, I wonder, do the side effects of the standard medication protocol start to outweigh the benefits?

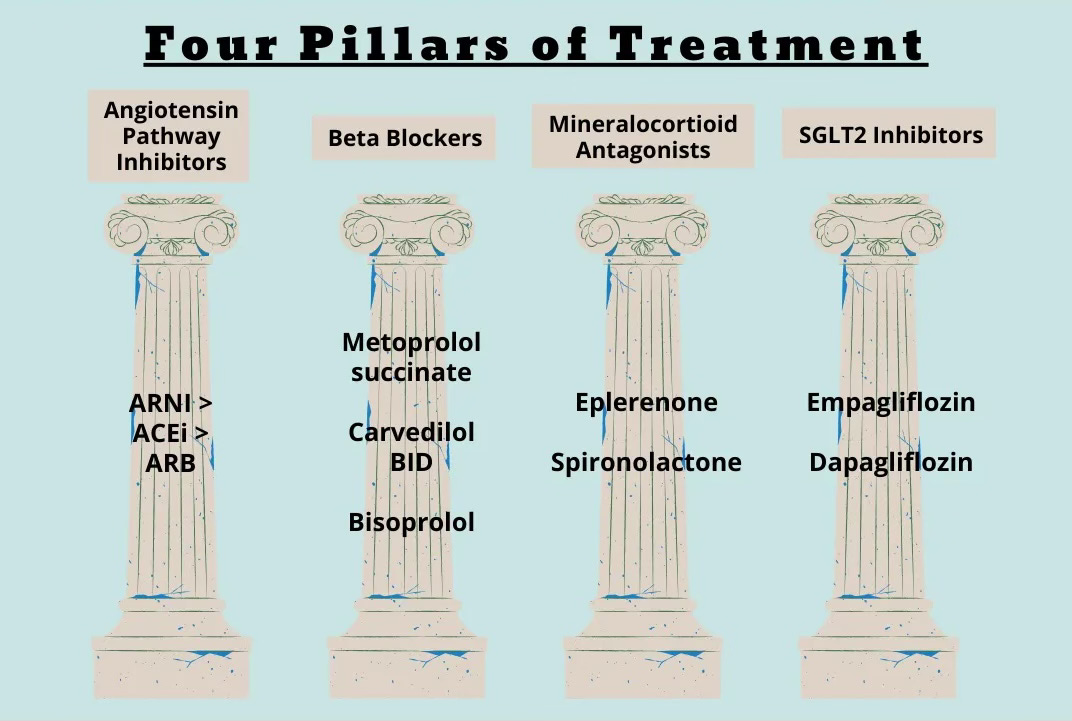

According to three excellent cardiologists I’ve consulted, the answer is never. Never! Nope. Don’t talk to them about dropping meds, or keeping the heart healthy through mere diet and exercise. Why? Because of an evidence-based protocol called goal-directed medical therapy (GDMT) in the 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. My prescriptions at discharge after SCA mirrored these guidelines. Although my EF had reached the all-important threshold to classify me as “improved,” the guidelines recommend continuing treatment indefinitely as if EF is still reduced. I promptly failed to tolerate two of the pillars (one drug sent me to the emergency room), and proceeded to fail a few potential replacements, as well. Such adverse reactions to GDMT are typical of female patients (Circulation, AHA). After much trial and error, I settled into life on teeny-tiny doses of just two of the four pillars. So, I can forget about getting approved to go off yet another drug.

I see where my doctors are coming from, I really do. For one thing, I’m a walking liability. Also, my cardiologists are trained to be specialists of the heart. They are not trained to understand all the quality-of-life impacts of being on a beta blocker longterm, as a female, while going through perimenopause. The entire GDMT protocol is based on clinical trials with disproportionately few female participants, despite the fact that heart disease is the leading killer of women (Go Red for Women; European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing). Faced with a dearth of evidence-based research and lacking a gender-specific protocol, doctors extrapolate as best they can. This “extrapolation of study results from predominantly male trials to women…leads to more side effects and potentially worse outcomes” (American Heart Journal Plus).

As I attempt to make educated decisions about what’s best for my body’s complex system in its current context, one important data point is the serious trouble I’ve had feeling joyful since surviving SCA. The better I got physically, the more out of sync my bleak emotional state felt with my reality. I’ve gone through the motions, of course. I’ve done all the things. I’ve consulted all the experts. I’ve attempted all the dietary changes. I’ve taken all the antidepressants. My saving grace is that I feel connected to my loved ones and my desire to help others. So, I keep going, mostly out of sheer duty, rarely feeling excited about my own future since being lucky enough to be gifted one. There’s a special sort of shame in admitting that. Who am I, a so-called “miracle,” not to feel 100% grateful all the time? Who am I, to complain?

I’m not writing this to complain. I’m writing it to explain why I made the momentous decision to go against standard protocol. If this is a bad move, I trust that my body will let me know. In the meantime, something had to give.

Almost one month ago, I broke up with my beta blocker, metoprolol. I have experienced no heart-related surprises or withdrawal symptoms, and I’m happy to report an immediate boost in energy and mood, decreased brain fog, and better focus. Being a woman in her early forties, every day is a different hormonal story and I never know what part of my emotional/physical landscape is due to those fluctuations. It will take a few cycles to determine whether the positive shift is lucky chance, some sort of reverse-placebo effect, or the effect of withdrawing a beta blocker. For now, I can tell you that my spirits have soared. The difference since I stopped taking that tiny pill is radical. Perhaps this is just what life feels like when my heart is allowed to beat fast enough to adequately supply my brain with oxygen?!

I hesitated to write this post because I do not want to be misunderstood as being anti-medicine or even anti-beta-blocker. Beta blockers are a class of medication that saves many lives. What works for me probably will not work for you, because we have different bodies. If your medications are therapeutic, that’s fantastic—take them! For my particular brand of heart failure, there is just no real consensus about what “therapeutic” looks like. Metoprolol’s protective effects in HFimpEF are unclear at best. Meanwhile, unintended consequences of long-term use abound. Beta blockers cause unpleasant central nervous system side effects for many people. Women are known to be extra sensitive to metoprolol. Yet I was told to take this pharmaceutical for life following the mysterious onset of a new disorder, based on standard protocol that may or may not apply to my own poorly-understood situation. Hold on, I think I’m having déjà vu. It’s kind of like that time I suffered through anti-epileptic medication for several years because I was told I had epilepsy with no known etiology, all of the sudden, at age 34…and then when I finally got bad enough to be admitted into an inpatient monitoring unit for a multi-day EEG at age 39, doctors discovered that I did not have any of the epileptic discharges those medications treat. As I weaned off two powerful pharmaceuticals, I not only had zero seizures, but the symptoms that landed me at NIH in the first place dissipated. (Read the full story here.)

Still, after what I’ve been through, I believe in medicine. Modern medicine saved my life. So, I toughed it out on metoprolol for two years. At some point, though, I had to consider that my inability to acclimate to this drug might be a sign that my body knows what it needs—and that metoprolol, or the GDMT approach, ain’t it.

The cool thing about science is that it’s always improving, and the latest research may back up my instincts. According to a study published in JACC: Heart Failure last month, I align well with the clinical profile of a “low-risk” HFimpEF patient (see illustration below): EF > 50%, no worrisome clinical symptoms, normal imaging and ECG, normal BMI…the only question is etiology. If my cardiac arrest and all former episodes were caused by viruses, as is currently theorized, then I likely have a “reversible” etiology and ceasing heart failure treatment makes good sense.

In a perfect world, I would not be on my own with this decision. Specialists would confer with each other on integrated teams designed to treat patients like the full human beings they are. Symptoms like depression would be weighted as heavily as ejection fraction, because everything is connected. Doctors would keep in mind how much our emotional state impacts our hearts, and vice versa. In mental health counseling education today, much lip service is given to the biopsychosocial model: “a dynamic, interactional, but dualistic view of human experience in which there is mutual influence of mind and body” (Annals of Family Medicine). This philosophy, aimed at reversing “the dehumanization of medicine and disempowerment of patients,” is not new; George Engels first proposed it back in 1980, a few years before I was born. In practice, though, our medical system runs on old rails. The field of cardiology insists on its four pillars of pharmaceuticals for everyone with heart failure even though doctors rarely prescribe all four and patients can rarely tolerate the full cocktail if they do.

As someone with multiple chronic diagnoses, I traipse back and forth between specialists of body and mind, trying to piece together my options. Ultimately, I’m left to my own devices when it comes to achieving the one goal I wish that all my care was directed towards: feeling better. Medicine really struggles with this being my main goal. After all, how is “feeling better” measured? By a BDI or PHQ-9 score? By time between loss-of-consciousness episodes? By my performance at work or grades in graduate school? By my ejection fraction? By my bloodwork? By the number of days or hours until my death?

No, feeling better is best measured in glimmers, in how well I’m able to appreciate and enjoy the good things that life affords me—the wildflowers blooming on a trail, the berries ripening around my yard, the rain on our metal roof, my husband’s hand in mine, my puppy’s contented sigh while he lays his head on my lap. I know I’m on the right track when I notice and enjoy these blessings. I worry when I feel like I’m squinting to see them through a dense fog.

The two years since my heart failure diagnosis have largely been a matter of fighting that fog. Until I won that battle, I did not consider myself a medical success. Now, as I enjoy summer with family and friends, and spend yet another week learning about mental health and practicing yoga, I revel in the connectedness that I spent years building. All the same external problems remain. My heart will never be the same. I have lots of tough days and bad moments. Yet I often find myself thinking: this is it. This is the life I survived for. I can taste the fullness of recovery that goes beyond remission of seizures or syncope and amounts to what I can only describe, self-consciously, as spiritual wholeness. I would take one day of this feeling over forty more years in a pharmaceutical-induced haze.

One afternoon a couple weeks after stopping metoprolol, I got caught in a sudden thunderstorm while driving down a gravel road. Cue flash flooding and hail. Billowing sheets of water caused whiteout conditions, such as I had previously only experienced in a Colorado blizzard. After years spent worrying about my heart, I was amused to consider that I might die from a random tree being struck by lightening and falling on my car. A tree did fall—actually, a few fell along my route, mere moments before and after I passed. As I huddled against the wheel, trying to peer into a powerful, all-consuming waterfall that even the closest lightening flashes could not penetrate, I experienced zero panic. I am still at peace with death. That’s the gift of what happened to me in February 2023. Only now, I was equally at peace with living. For the first time in over two years, contemplating my own end was not accompanied by longing or relief; I preferred to live through that storm. I preferred to teach more yoga and complete my degree. I preferred to watch my hazelnuts form on the bushes. I preferred to arrive in one piece at the brewery that was my destination that day, so I could spend time with my hubby and some awesome friends. Even during that treacherous drive, I welcomed the joy of having a fully-functioning nervous system again, for whatever reason, and hoped that the withdrawal of one half of a tiny heart pill continues to make such a big difference.

I offer no medical advice in this or any post and expressly DO NOT recommend withdrawing a medication without doctor approval. Please remember, I’m just some random person on the Internet and/or your sick friend who gets desperate and tries things. Take everything I say with a grain of salt, and please know that I spoke to many trusted specialists about my plans, even if I ultimately went against some of their advice.

The lesson here is that wellness is about much more than the optimal performance of a single bodily organ, even if the organ in question is the life-giving heart. If you, like me, want to feel better, why not ask yourself: what you are doing (or not doing) that impacts the functioning of the whole? I refused a treatment that does some beneficial things for one organ because it had a negative impact on my overall system’s ability to function and regulate itself. I took this risk because I was willing to have less time if it meant having better time. There’s healing power in remembering that only I, the patient, get to make such a choice. In doing so, I signified my commitment to enjoying life—and lo and behold, I enjoy it more. The noncompliant action of not taking a prescribed pill reinvigorated a sense of self-determination that I still possess, even through all these exhausting health debacles. Sometimes, for those of us living with chronic illness, exerting self-determination can be the most effective treatment.

And sometimes, no matter how hard we try to fix our crazy little bodily systems, things get worse before they get better. Maybe it took the devolution of 2025—the political, social, and economic upheaval of this longest of years—to push me to the breaking point, where I became so miserable that I was willing to take this particular medical risk. As always, our environment plays a huge role in our health. A lot of people I know are struggling these days. What changes will each of us make, to feel better?

This will take some time to digest. Clearly a lot of thought and research has gone into your choices, many others in similar circumstances of chronic conditions and medical therapies will relate. I like your close observations about the limits of the studies done, like numbers of female participants.

Lauren, Just now I had the opportunity to read this amazing post. Thank you so much!