Dancing with Seizure Drugs (Part II)

I leave NIH with more questions than answers...and maybe, just maybe, a fresh start

In Part I, I described my first few days at an NIH epilepsy monitoring unit.

Many times throughout the study, I asked myself why I volunteered to be confined to a small hospital room for an unspecified amount of time…to get woken up by alarms all night…to have electrodes glued to my scalp and hair…to sleep tangled in cords…to submit to video surveillance of my every move…and to be provoked into having seizures.

But a few times each day, during episodes or auras, or when various neurologists came to talk to me, I remembered why I was in epilepsy jail. I was desperate to find out what was happening to my brain.

When I first started having seizures in 2018, they were pretty clear cut. They generalized quickly into the stereotypical tonic-clonic (GTC) or “grand mal” you probably picture when you read the word seizure. Eyes rolled back, fell over like a tree trunk, convulsions, concussions, hours of post-ictal weakness and confusion…the works.

Since my cardiac arrest in February, I started having new episodes that NIH researchers hoped to classify. My new episodes didn’t involve loss of consciousness. Instead, they involved walking like a drunk girl, losing my ability to speak, and a left-sided weakness, tremor, and convulsions. My epileptologist suspected that I was having “focal motor” seizures and that my antiepileptic drugs were (so far) keeping them from generalizing into GTCs. If my epileptologist was right, NIH doctors could use video EEG to correlate the outward symptoms (described in detail in a previous post) with abnormal brain waves. They’d be able to confirm the type of seizure I was having and determine where the errant discharges originated in my brain.

The episodes were becoming daily affairs, and I was already taking the highest possible dosages of medication I could tolerate. There was a chance that classification might lead to discussing more invasive interventions, up to and including brain surgery.

As fearful as I was about what doctors would find on the EEG, I’d been living with epilepsy for five years and had never had a thorough investigation. I wanted answers.

Before I fill you in on the findings, we need to pause to tackle a very important question. What is epilepsy?

I’ve been trying to figure out the best answer to this question for years, and I’m still trying. Here are a few starter definitions:

ep·i·lep·sy (noun)

a neurological disorder marked by sudden recurrent episodes of sensory disturbance, loss of consciousness, or convulsions, associated with abnormal electrical activity in the brain

Google Dictionary

Epilepsy is a brain disorder that causes recurring, unprovoked seizures. Your doctor may diagnose you with epilepsy if you have two unprovoked seizures or one unprovoked seizure with a high risk of more. Not all seizures are the result of epilepsy.

Epilepsy is a chronic brain disorder in which groups of nerve cells, or neurons, in the brain sometimes send the wrong signals and cause seizures. While any seizure is cause for concern, having a seizure does not by itself mean a person has epilepsy.

NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

These definitions fail to capture that in real life, epilepsy is often a default diagnosis after ruling out a few easy-to-find potential causes for a person’s episodes. I’ve spoken to dozens of people in support groups, and there’s a common pattern amongst the 70% of us whose epilepsy doesn’t have any known cause. Here’s how it usually works:

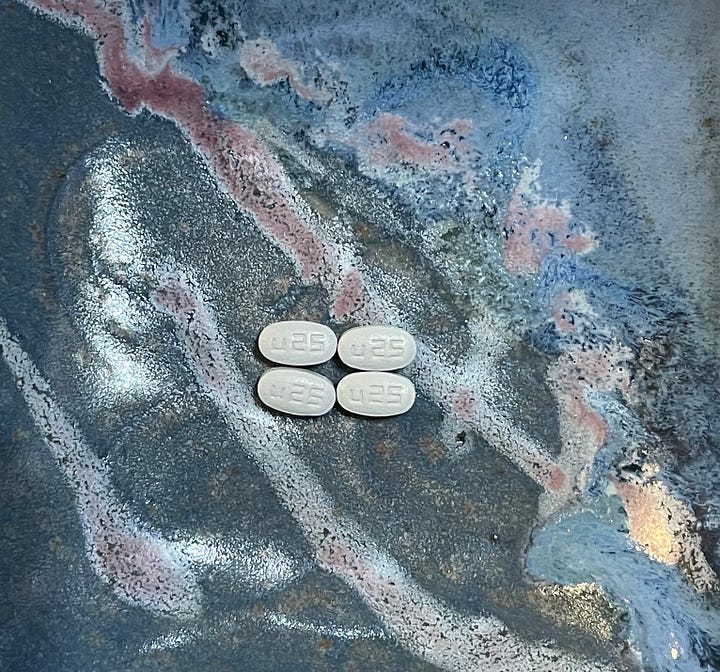

After the first or second “unprovoked” event that doctors suspect was a seizure, you’re put on antiepileptic medication. Most likely, they start you on Keppra, the cheap stuff that causes mood issues (“Kepprage” is a common complaint, as is depression and suicidal ideation). It also has a host of other systemic side effects, such as infections, nasal congestion, and vision changes (I had to start wearing glasses within a month of starting Keppra!)

Putting people on medication right after their second seizure is a safety measure that doubles as another step towards diagnosis. If the seizures continue after trying a couple of antiepileptic drugs, doctors start to wonder if epilepsy is really the problem. They may do additional testing (such as invasive EEG, SPECT, or fMRIs) to try and figure out what’s going on. The extent and type of testing really depends on the clinical suspicions of your epileptologist. One very accomplished epileptologist recently told me she’s wrong sometimes. But she also explained her clinical suspicions better than most. Diagnosing drug-resistant (suspected) seizures is not an exact science.

On the other hand, if the seizures stop with your first med or two…welcome to limbo land. Since antiepileptic medications seem to work, doctors assume you probably do have epilepsy and aren’t inclined to take you off of meds to test that theory further. The problem this creates is that you’ll never know if the meds are working or if your body was just naturally done seizing anyway. Maybe you had some passing ailment that resolved after several months. Seizures have many mimics—maybe you suffered one of those. The only way to find out whether you need to stay on seizure meds is to taper off, risking more seizures. The potential for injuries, career interruption, social embarrassment, loss of driving privileges, and even SUDEP (Sudden Unexpected Death in People with Epilepsy) usually isn’t worth it. Many people stay on seizure meds for decades, never knowing why their seizures started or even if they’d still have them without the pharmaceuticals.

I hated Keppra enough to convince a neurologist to let me taper off six months after starting it. I just couldn’t believe I had epilepsy all of the sudden at age 34. Don’t most seizure disorders pop up in the young or elderly? My neurologist agreed that this was highly unusual, and we tapered just a tiny bit. And a few weeks later, under extreme relationship and career stress, I had a third GTC. My neurologist concluded that I did indeed have epilepsy. He added the diagnosis to my permanent medical record and returned me to my initial dose of Keppra—and to all the depression and fatigue it brought with it.

I had a few short outpatient EEGs in the early days, but they were inconclusive. This didn’t phase any of my neurologists. Many people don’t show epileptic discharges between seizures, or even during focal seizures. An abnormal EEG with epileptiform activity can confirm a diagnosis of epilepsy, but a clean EEG doesn’t really mean much. I was told I needed to prepare to remain on drugs for the long haul. When I complained of the severe depression I was experiencing on Keppra, I was prescribed Zoloft to take in addition too Keppra. It gave me amazingly bad headaches, so I had to make do with psychotherapy to help me accept a future of gray, brain-foggy dullness.

I started to reorganize my life around my diagnosis. I sold my car, moved to be closer to public transportation, dropped out of my second masters program, and adjusted my career goals. My partner at the time struggled to stand by me, given my less-than-superhuman response to these life impacts. Soon, I added a breakup to my list of epilepsy adjustments.

As the world entered the pandemic lockdown, I was a shell of my pre-epilepsy self. I could accept a lot about my fate, but feeling that my central nervous system (CNS) was wrapped in cotton balls and knowing this was the price I had to pay just to regain my driver’s license and continue eking out an independent living, all so I could wake up each morning and poison my body with more drugs that made my CNS feel like it was wrapped in cotton balls…well, you see how one would get a little blue. Ok, maybe very blue.

Gradually, bit by bit, Father Time and a few loyal friends helped me carve out a life that felt bearable. Things started to improve as I got my license back, trained my service dog Nosie, and took him hiking in the Virginia mountains every weekend. Then, I found a much stronger partner and started building the love and the home I wanted. The depression was still there, but I wasn’t alone with it.

And I didn’t have any more seizures while I took Keppra. For years. So my diagnosis remained unquestioned.

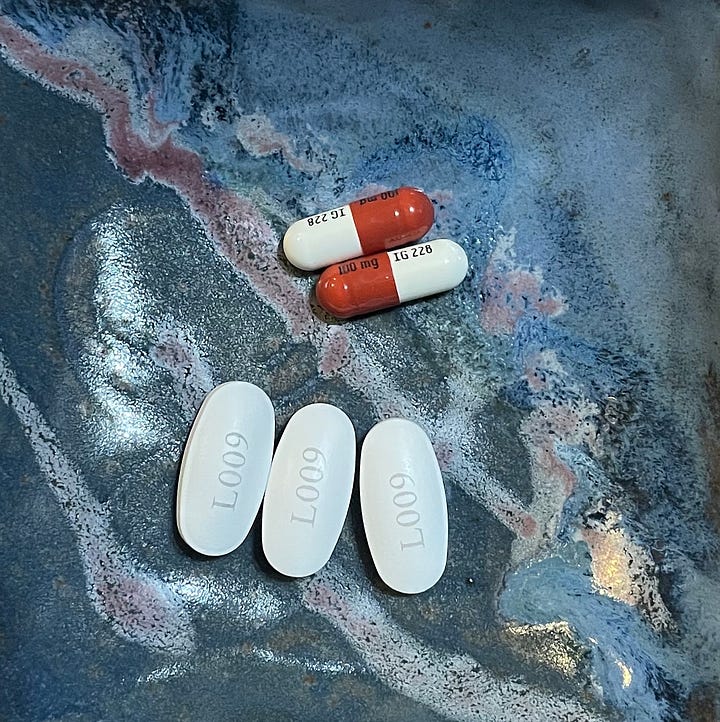

Even when Keppra failed to do its one job after I got COVID, nobody questioned my epilepsy diagnosis. If anything, the breakthrough seizures that led to my sudden cardiac arrest confirmed my epilepsy was still there, lurking under 1500 mg/day of CNS-squashing drugs. A few months later, despite being on three times the meds I’d taken prior to cardiac arrest (and feeling three times as depressed), I started having the new episodes where I walked and talked funny but didn’t lose consciousness. Was my condition morphing? Was it epilepsy itself, brain damage from the cardiac arrest, PTSD, medication side effects, or something else?

This is why I reached out to NIH. It’s what their epilepsy team lives for: to classify the confusing, drug-resistant epilepsies.

Ok—so back to the week-long EEG. What happened at NIH was a big deal. A major plot twist. What happened was nothing. Researchers saw NOTHING to indicate epilepsy. For seven days, my brain just lay around being a totally boring, normal brain. Even when I had my new episodes on camera…even when they took me off all of my antiepileptic drugs. It’s totally possible for focal seizures to evade detection, but it’s also telling that I didn’t have a GTC after rapidly dropping dosages in half and then going drug-free the next day. I remained off drugs for a couple more days. And not only did I not have seizures, but for those two days, I lost the speech arrest and movement disorder that sent me to NIH in the first place. My erratic heart rate stabilized a bit and the low-bpm alarm sounded less at night. My systolic blood pressure finally started pushing into the low 100’s a few times per day.

I felt like a new woman.

Researchers raised the possibility that not only were my new episodes non-epileptic, but that perhaps all of my previous GTCs were provoked by illness or external factors. If that were true, do I technically qualify as having epilepsy?

Support groups and online forums are full of stories of flip-flopping diagnoses. People often get thrown from epilepsy to other diagnoses and then back again. One person I met flip-flopped between epileptic and nonepileptic seizure disorder diagnoses eight times! They’d done several EEG studies along the way, which I think says a lot about the use value of external scalp EEGs.

I have one more important definition to throw at you. “Nonepileptic seizure disorder” is as big an umbrella term as epilepsy, and it includes:

Provoked seizures: All of us have the mechanisms to seize under the right conditions, so having one seizure—or multiple tied to specific causes—doesn’t mean someone has epilepsy. Examples include febrile seizures, seizures in alcoholics during withdrawal, seizures during/after sudden cardiac arrest, diabetic seizures, celiac seizures, seizures after traumatic brain injury, or seizures during any severe illness. Etc, etc.

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES): PNES is classified as a conversion disorder in which the body protects the mind from re-experiencing trauma. It’s often the next default when the default diagnosis of epilepsy is disproven by a video EEG study. [Note: This means the line between epileptic seizures and PNES shifts with advancements in EEG technology. Sometimes someone is told they have PNES because an external EEG showed no signs of epilepsy but then an intercranial EEG sees things the scalp EEG couldn’t, thus reverting the diagnosis back to epilepsy...]

An NIH doctor told me that about one third of patients who come through her inpatient monitoring unit don’t show signs of epileptic seizures. I joined that cohort.

Meanwhile, lack of sleep, showering, exercise, and fresh air all took their toll. But as Zonisamide and Briviact faded from my system, I got to experience the self underneath those psychoactive drugs for the first time in a long time. Then, on the morning of the day before I got to go home, a nurse came in bearing a dose of Briviact.

My history was too complex and seizure-ridden for doctors to feel comfortable sending me home un-medicated. I got that. But even though they’d warned me they’d be bringing back the drugs on my last full day of jail, I wanted to cry as the nurse handed me the pill. I hear you, I silently reassured my panicked brain, taking the pill from its little plastic cup. I’ll come back for you as soon as I break out of this joint.

Instead of spitting the pill into a tissue when the nurse’s back was turned (a move that would have been recorded by the cameras anyway…sigh), I swallowed it. The nurse saw me tear up, and I admitted that I was upset about returning to Briviact. I asked if there was any way I could get a smaller dose that evening. She called the epilepsy specialist to discuss my fear that the medicine would make everything worse again. “The patient is probably correct,” the doctor said. She ordered me a slightly lower dose while at NIH and wrote my outpatient prescription so I’d have even smaller pills for tapering off after I got home.

NIH doctors couldn't erase my epilepsy diagnosis on the basis of one week of clean EEG data. There’s still the chance that if we’d caught a GTC, the expected discharges would have appeared. But we didn't, and their clinical suspicion was that maybe I’m not that epileptic.

Whatever else is in play here, antiepileptic meds have greatly impacted my emotional state and physical wellbeing for five years and then failed to prevent the seizure that almost ended my life. After tasting a couple days of freedom, I decided that the treatment has likely been worse for me than the disease.

I resolved that when I got home, I would taper off antiepileptics fully. If I do have epilepsy, my body will sure as heck let me know. If I start having GTCs, I can always go back on drugs. I’m not working or driving at the moment, and I have a supportive spouse. I’m in the lucky position to be able to learn the hard way.

My predicament made me think of the J. R. R. Tolkien quote on a monument in the gardens around the Safra Family Lodge at NIH: “All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us.” I knew I would be putting my life in danger by going med-free as a survivor of status epilepticus and cardiac arrest. And that’s in addition to the general risk of injuries from GTCs. At the same time…what’s the point in prolonging a life you don’t want to live? Of all people, I can say this, having so recently toyed with death. Chris, who has witnessed me have a seizure and seen my heart stop beating, has also seen me attempt several different seizure drugs. He’s on board with trying to taper off.

Before I die, I want to spend some time with my actual brain. I want to free my CNS from its cotton-ball wrapping and know myself. What’s been hiding beneath a pharmaceutical fog for the past few years? Are there monsters under my bed? Only way to find out is to look.

In our final consultation on the day I left NIH, doctors agreed this course of action was reasonable. Especially because I’d continued to show fewer signs of speech arrest and tremors as the meds left my system.

Medication toxicity became my number one hypothesis. I went through the motions after leaving NIH, including wearing a heart monitor taped to my chest for two days to see if there might be a cardiac cause for some of my symptoms. One NIH neurologist (not on the epilepsy team) suggested that I might have a rare form of complex migraine and encouraged me to talk to my migraine specialist. I did so, and we agree this might make sense. I’ve had migraines my whole life and experience visual aura, loss of speech, and sometimes even facial asymmetry with severe headaches. It’s possible for migraine to mimic stroke and seizure.

Although I left with more questions than answers and a long list of follow-up appointments, the epilepsy monitoring unit was worth it. It would have been irresponsible and terrifying to lower my meds outside of a hospital setting. Also, I got a glimpse into what healthcare could be if profit wasn’t the main driver. I loved my nurses—laughing with them, learning from them, and watching their huddles between shifts. I loved the detailed explanations from NIH doctors and the time they took to chat with me each day to consider all of my concerns. It was certainly a week I’ll never forget.

Back at home, though, I realize how little I really learned about my body in epilepsy jail. I feel my faith in medicine sink to an all-time low. Modern, Western medicine saved my life in a crisis. Modern medicine created Ubrelvy, my all-time favorite pharmaceutical because it aborts migraines before I feel compelled to take an ice pick to my eyeball. But medicine has proven pretty worthless at treating chronic illness. The Eastern concept of “mind-body” makes more sense to me than a harsh demarcation between the physical and the mental/spiritual. Treating myself in pieces hasn’t gotten me very far. What would treating myself as an integrated whole look like?

I’m not sure yet, but I do know that answering this question starts with leaving behind a few daily meds.

Three days before this post was published, I finished weaning off seizure meds. Everything about life feels more interesting now. I notice a hum in the air as my senses snap back to attention. At the same time, my anxiety increases. I fear seizures constantly and carry rescue inhalers with me everywhere. I’m hoping that feeling on edge lessens with time spent enjoying the simple things: doing yoga in my sunny backyard, kissing my husband, walking my dog along the creek, and tending my autumn garden. I ask myself, how many seizures per year would it take to give up all this sensation and joy for the cotton-ball wrapping again? It might take quite a few.

And as I type these words, it’s been over a week since I experienced speech arrest or convulsions. The medication side effect theory strengthens.

Everything has side effects. I have learned that no matter what the doctors say I should be able to handle, and no matter what the pharmaceuticals promise, everything has side effects. Treating epilepsy pharmaceutically gave me side effects that mimicked the condition itself! Not treating epilepsy might have grave (pun intended) side effects, too—only time will tell.

As a kind neurologist said last week before reluctantly blessing my desire to taper off drugs: “You’re the boss. There’s no one-size-fits all treatment.” If I do medicate against epilepsy again, at least I will know my body a little bit better first. And it will be my own highly-informed decision.

Reminder: This is a patient-experience piece that is in no way intended to convey medical advice. Go to your doctor (or, like me, 10 specialists) before messing with your prescriptions.

A surprising portion of seizure patients admitted to EMU are discharged with the same sort of result. This outcome was kinda suspected for you as well, which, on balance from a certain perspective, is a good thing.

I see in you a brave look forward willing to take this a liberation.

I would say NIH docs are going to be way too lawsuit averse to let you go without meds.

In some of the most exciting areas of science, neuro being one of them, there is this draw of the unknown, and the unknowable, and in the clinical world, the unknown unknowns. Sometimes we have to humbly reside less than comfortably with, 'don't know'.

Here you document your living trek over that wilderness. Which, I must say, is masterful.

This writing is engaging and flows. Informative, educational. You use very good references and hyperlinks, a person knowing very little could learn a lot. And get very scared. But it's the truth.

You're doing it right, and well. Keep it!

Further a model for how to substack!

Lauren,

May you continue to be seizure free! You reinforce the idea that we all need to be our own fierce advocates in the world of health-related issues. I admire your courage and willingness to share your experiences. Continue to heal your mind and soul as well as your body.

Love and hugs to you,

Leigh