Fear Itself

Healing from chronic illness requires testing and re-testing our personal edge

I’m afraid of black bears.

I’ve only seen one bear while hiking, and it was far away. It also looked larger and less cuddly than I’d expected. I never thought much about black bears when I started hiking the Blue Ridge Mountains several years ago, having spent much of my childhood in Colorado (where there are actual predators). I’d been terrified of mountain lions, growing up. I mean, they blend perfectly into the landscape and leap onto hikers from behind! After seeing one ginormous black bear lumbering silently through the mountain laurel, I suddenly felt like there was a new potential risk factor to hiking in Virginia.

I recognize that this makes no logical sense. Black bears are rarely aggressive. According to BearVault, the makers of my expensive bear canister for backpacking, “since 1784 there have 66 fatal human/bear conflicts by wild black bears. Less than a dozen non-fatal conflicts happen each year, and the vast majority of encounters end with zero bodily contact.” Given that I keep my dog leashed and don’t sleep with food in a tent, there’s really no point in losing sleep over a scary black bear encounter. And yet that is exactly what I did one night this week.

I crossed a major item off my bucket list by taking my service dog, Nosie, on a short solo backpacking trip in Shenandoah National Park. A few months ago, I would have assumed that as a cardiac patient, hiking 7.5 miles with 28 pounds on my back would be the hard part. “It’s really the psychological aspect,” a female Appalachian Trail through-hiker said recently on a group hike, when asked what the hardest part of her 2,190-mile journey had been. I’d always assumed the hardest part would be physical, and I wondered what she meant by her comment. What did this tough outdoorswoman fear?

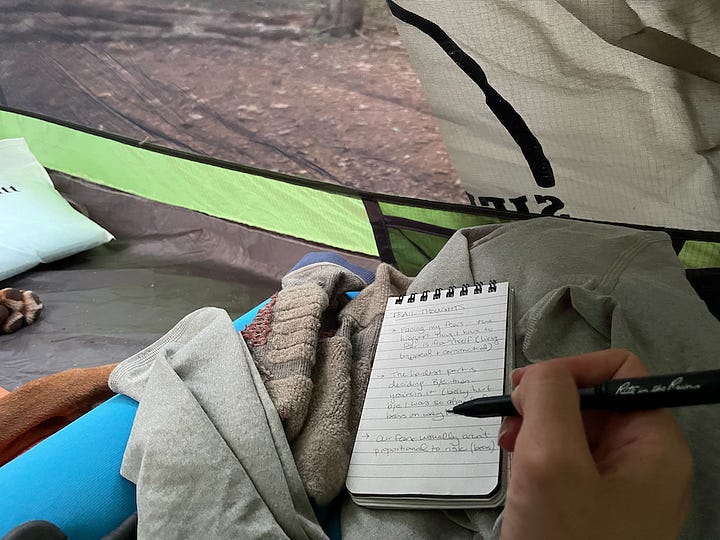

When I messaged Chris with my satellite device at dusk, letting him know that I was safely in my tent and headed to bed, I wasn’t yet scared. I wrote in my journal, under the title “Trail Thoughts,” that the hardest part of doing this had been deciding. I was thrilled about the physical feat, completing an activity that would have been challenging for my pre-cardiac-arrest and pre-epilepsy body. I applauded my damaged, measly heart and felt proud that while it might objectively struggle more, it was also capable of doing so much more with what it has.

Then night fell, the forest woke up, and all positivity and reason wafted right out the big mesh window of that tent.

As I lay in the deepening darkness listening to bobcats yowl, coyotes yip, owls hoot, and unidentified nocturnal beasts flit through our campsite, I clutched Nosie’s quivering leg and thought about bears. Every time Nosie stood up or seemed especially on edge, it was a bear I expected to see standing over the fine mesh roof. Being attacked by a human male may be more statistically likely, but I hadn’t seen a single human hiking this trail in the daylight. I couldn’t imagine that someone was going to hike through pitch darkness into my neck of the literal woods, on the off-chance some lone female with a surprisingly wimpy dog might be lying vulnerable and alone. Plus, the bear spray I carry works on all mammals.

I had decided, and now I was in it. This too shall pass, I tried to soothe myself. Then Nosie gave two short, stressed whines in a pitch I’d never heard before, and JUMPED out of his skin like an animal had surprised him right outside our zipped door. My heart leapt with him. “I’ll never make us do this again,” I promised Nosie, petting him in an attempt to ease his quaking body while talking loudly enough to alert the surrounding animals that there was a Big Scary Human with Tools in this tent. “We just have to survive this night. The hours will pass.”

They did pass, albeit slowly. I counted them down one by one. Every break in the nocturnal melee that allowed Nosie to drop his head and relax his perked ears would afford me a brief cat nap. Then a howl or a hiss, and I was staring back into the eerie, swirling branches above the mesh roof. I listened to the wind wend its way across miles and miles of treetops until moments later, the branches above me shuddered and I felt a short, soft burst of air through the sleeping bag liner.

Each time I shut my eyes, I saw bears. Big bears, little bears, bears standing on their hind legs. Our fears aren’t usually proportional to risk. I’d taken every precaution, buying a quality BearVault and placing all food and toiletries inside. The container was stowed just out of sight, down by the creek where I’d fed Nosie and me our dinner. And yet I dreamed of a bear pawing at me through the tent. When I woke up, I reminded myself that I know what death is like, and I’m not afraid of death anymore. So why fear a highly improbable and unprovoked bear attack? Besides, if I don’t risk bears, I stay stuck at home forever, a slave to my shelter. If I wasn’t willing to suffer the anxious tummy ache that struck right before I left the house, backpack loaded, I’d never know if I could do this…or what that through-hiker meant about the psychological part of sleeping in the woods being the hardest. If there’s one thing I felt in that tent, it was utterly and so, so vulnerably alive.

It went on like this. At some point, a migraine started to weave its way around my left eye. I’d left my medication in a toiletry bag in the bear canister—like hell was I going down there in the dark to get it. I lay, doused in sweat, no longer sure if it was caused by pain, fear, or the humid, too-warm woods. Dawn crept up on us much more slowly than night had fallen. By the time things settled long enough for me to sleep a full hour, I woke to a forest brightened. I could see clearly out of the tent. The tree branches looked like branches again, not odd, monstrous shapes. I checked my phone: 6 AM. Of course. I woke up at the exact same time I do everyday. I immediately started packing.

The hike out should have been easy. I’d hiked 4.5 miles of the loop the day before, so only 3 miles remained. My pack was a lot lighter after consuming most of our food and water. Somehow, though, it was the toughest slog of my life. The sleeplessness and muggy morning air combined with my migraine and gnats that kept diving directly into my eyeballs. Every five seconds I’d stop, shout profanities, and dig another one out of an eyelid or an ear. My water nozzle intermittently and inexplicably stopped working. It was also straight uphill to the parking lot off Skyline Drive where I’d left the car. About halfway, I felt a little faint and leaned my bag on a log to catch my breath. Looking down at the trail, my vision blurred and a short burst of nausea almost knocked me from my perch. But I’d decided, and now there was nothing to do but finish. The Iridium satellite network hadn’t allowed me to message Chris this morning. My long-suffering husband was waiting for a safety check. I had to make it, low-normal ejection fraction, cardiac/seizure history, bear fears, and all. So I just…did. I’m not sure how. I just kept placing one foot in front of the other, the miles passed, and I made it. But not before a strange run-in with a young male deer who wasn’t as afraid of me as I would have liked him to be. Dark eyes under large antlers glared at me and Nosie as we passed. I thought of all the ruckus in the night, and that buck’s steady gaze. Little girl, I thought, you’ve found your edge.

So now I know. I really don't like sleeping in the woods by myself with my vizsla. I’d backpack again with a buddy, and Chris and I have big plans for car camping in the new palatial tent we bought on sale at REI this month. I have lost all desire to solo backpack the Tuscarora trail, though, or even the local Massanutten or Dolly Sods. Chris is relieved—he was a nervous wreck while I was sleeping in the forest. Bears were not on his list of concerns.

We all have fears. Some of them are better founded than others. We don’t even give a thought to many of the riskiest things we do, such as driving down the highway. Meanwhile, we obsess over every little chemical in a household cleaner. We fear plane crashes, while ignoring heart disease, the leading cause of death for the past 100 years.

“We are all terminal patients on this earth” (Jaouad, Between Two Kingdoms, p. 119). I remember this fact better than most, because there are things from which I won’t ever recover. I carry hope, though, that it’s possible to heal. I live very comfortably with death. I walk hand-in-hand with the ghost of the self I was before my cardiac arrest, hyper-aware of where I’ve been and where I’m ultimately going. I still fear many things in this life, though. I fear physical pain and…well, and fear itself, to quote FDR. That is, I fear living in a tiny box of my own making, my actions and decisions determined by fear instead of knowledge, pleasure, and meaning.

Off meds, I continue to strengthen in many ways, both mentally and physically. I seem to be reaching a point in my recovery that requires me to test and re-test my boundaries, finding my new edge and waltzing right up to it. Or sometimes, as with backpacking, tiptoeing right past my edge to see what’s really there and if it’s worth being scared to experience something new.

There was a time last year that being home alone for more than an hour was scary. Just existing felt hard, and so did being alone with the knowledge that I’ll never know quite what happened to my body on February 7th, 2023 or why I was so lucky—why my insanely long survival chain worked. For months, I could coexist with the combination of oppressive knowledge and eerie uncertainty only in my own home, within arm’s reach of my husband and/or Nosie, and with lots of stuffing-down of the most difficult feelings through excessive baking of gluten-free sweets. Now, I can put those fears in a very large backpack and take them with me. They don’t weigh me down too much to hike through the forest for hours. I slept in the woods alone, far from a car or WiFi or any amenities, as a cardiac survivor and epilepsy patient. Me, a 118-lb female. I needed to know what was out there. There’s so much I don’t control about my conditions, my past, and my future. My life feels a little less constricted because I decided to face my fear of bears—as well as all the more likely scenarios (snake bites, human attacks, broken ankles, and cardiac events) that I can only partially prepare for and prevent on the trail.

As I crested onto Skyline Drive on Wednesday and approached the beautiful, shining, beacon of my car, that luxe carriage that would take me to a nearby wayside station with gleaming, flushing toilets and hot coffee, gratitude rushed into the tense spots in my shoulders and back. Warmth, joy, and freedom flooded my system. I won’t be backpacking solo again anytime soon, but on the way home I was filled with words that needed to be written down. After many weeks spent actively living but feeling bereft of thoughts interesting or conclusive enough to record anywhere but in my own journal, I felt the familiar itch. This was an experience to share. I also found myself listening to music more over the last couple days—something I've struggled to enjoy since my cardiac arrest. I feel more certain that my career isn’t yet over. As I continue having coffee dates with former colleagues and friends, pondering my next moves and whether, or how, I’ll work again, I am trying to keep close that rush of joy, the lightness of tossing my heavy pack into the backseat and driving back to civilization having fully tested my mettle.

There is creativity that can only be born out of trial. There are moments along the path to any important achievement that are tough to endure, and preparation (while important) can never guarantee success. The hardest part is deciding. Deciding to go. Deciding to live fully, instead of remaining trapped and constricted in a life that’s suddenly (finally!) too small.

Dedicated to the (Original) Ron Howard, my grandfather and an avid outdoorsman with plenty of his own backpacking horror stories.

This is great Lauren … it reminded me of a trip I took to Elmira NY years ago I was dropped off there at around midnight and had to walk to my destination which was several hours on foot in the early hours of the morning. It was most nerve wracking carrying a full pack through a dark woods when the road had narrowed to a single lane. As I passed through some large animals were moving nearby in the forest; likely deer but in my mind something far more sinister - bear or even worse another person. We all create paper tigers I guess … there is a short story by Stephen Crane called Open Boat … a number of people are stranded off coast after their ship sinks. They have to wait out the night there … there is a quote from that story that goes something like this, “A night in an open boat” is a long night. Indeed it is. Crane spoke from experience having been stranded himself after a ship sank. Suffering leads to spokespersonship.

Bravo for completing a big challenge. I did seriously cringe once I appreciated you were out there solo. Kissing the glass wall of disaster without a buddy.

And I don't quite get the bear canister thing. Must be a new outdoor marketing thing. As your data specified, encounters are rare. To so encourage you to leave your precious meds and scare you into thinking you needed to leave them far from where you needed them- potent misinformation in my opinion.

The dangers from our medical conditions will hurt us sooner.

Knowing this, however, you are a brave pioneer and explorer into new lands. Taking risks, facing challenges, discovering the unknown. Thank you for writing about it.